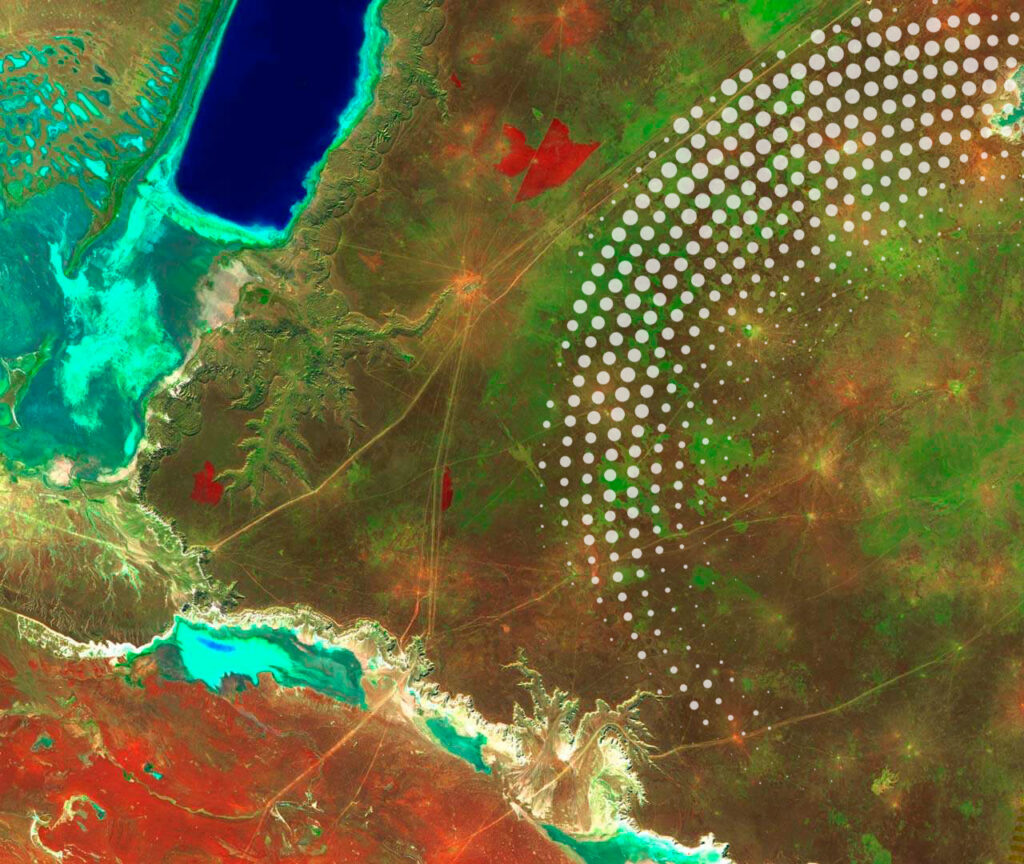

From the dense forests of Brazil to the deep Pacific ocean, our planet has an innate ability to remove CO2 from the atmosphere. For hundreds of years nature has acted as a shield, protecting us from the worst impacts of our own, ever-increasing emissions. Yet, there is a limit – nature cannot continually mitigate without receiving care and investment. While many are waking up to the power of nature in our global climate crisis, it’s still fair to say that its true value is not yet reflected economically.

However, we have tools at our disposal to help rectify this imbalance. Nature-based solutions (NBS) are one way to drive finance to conservation and restoration. These solutions involve working with natural ecosystems – such as forests or oceans – to address global challenges. The IUCN Global Standard expects NBS to provide a net positive impact on biodiversity, while simultaneously empowering stakeholders.

A similarly named subset of NBS is natural climate solutions (NCS). These are nature-based solutions that specifically address the climate crisis. They can be divided into two categories: those which avoid emissions from being released, for instance through the prevention of logging degradation or burning or existing forests, and those which remove carbon from the atmosphere via the creation of new, natural carbon sinks. Unlike NBS, the minimum requirement for NCS – as stated by The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) – is that they result in zero net loss for biodiversity. But regardless of whether a project is NBC or NCS, it should be high quality – its benefits should be real, measurable, additional and permanent.

The need for nature

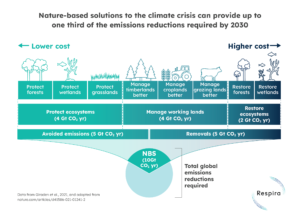

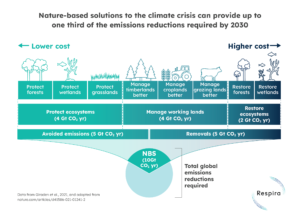

To keep 1.5°C in reach, the IPCC states that we must achieve net zero by 2050. Meeting this target requires rapid decarbonisation and extensive climate mitigation which is a huge challenge. But there is hope. It is widely agreed that the natural world can deliver up to one third of the climate mitigation required by 2030 (see picture below). Indeed, it has been calculated that if nature-based solutions are effectively deployed, it could be possible to reduce and remove at least 5 – and potentially 11.7 – gigatons of CO2e from the atmosphere every year.

Therefore to hold open the rapidly closing door on 1.5°C, we need to tap into this potential. But this requires sustained, financial commitment from global, national and corporate actors. At present, nature-based solutions receive approximately $133 billion of public and private funding every year. While this sounds substantial, it is, in fact, only a conservative 25% of the level needed if we are to reach our 2050 climate target.

The grave, green problem

Deforestation poses a massive threat to the world’s green carbon sinks. Currently most prevalent in the tropics, trees are felled at scale to make way for cattle ranches, soybean plantations and to meet global demand for timber.

Deforestation places the world’s future in jeopardy. Not only is deforestation a major threat to global biodiversity, but it also reduces the capacity of the world’s forests to capture carbon. Trees naturally take in CO2 when they photosynthesise and, without them, we would have significantly more carbon in the atmosphere than we do today. But when trees are cut and burned, they release carbon. Tragically, the volume of carbon currently emitted from global deforestation and degradation is second only to fossil fuel combustion. Without action to halt deforestation, our greatest carbon sink will remain a significant carbon source.

The world’s forests are also critical for global temperature and rainfall regulation. Water evaporating from the leaves of trees creates a cooling effect on the surrounding environment, while the unevenness of forest canopy’s alter wind speeds, further dispersing rising heat. This ability of trees to cool the planet means that tropical deforestation actually contributes 50% more to global warming than straight up carbon accounting suggests.

The great, green solutions

To prevent deforestation and safeguard our natural carbon sinks, we must take action. It is estimated that 62% of the reductions and removals facilitated through NBS will come from forests and we know that these solutions are here now and ready to scale.

Conservation

It doesn’t make sense to be losing forests faster than we are planting them, in the same way as it makes no sense to leave the taps running when trying to drain a bath. Moreover, newly planted trees take many years to achieve the same carbon storage capacity as existing, mature forest. Indeed, some Amazonian trees are hundreds of years old so are completely irreplaceable in the window left available to us to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Forest conservation, or REDD+, is a well-known method through which to generate nature-based carbon credits based on emission reduction. Independent assessors verify how many tonnes of carbon are stored in a particular landscape’s trees. By measuring the area of trees that has been protected from being cut down, the amount of carbon that has been stored due to a project developer’s conservation can be calculated. From here, a conservatively corresponding volume of carbon credits can be sold via the voluntary carbon market.

Amid recent critiques, recognising high-quality forest carbon credits is of utmost importance. This means that the conservation would not have been possible without the finance generated through the sale of carbon credits and that the project is, as far as possible, permanent. High quality REDD+ projects typically withhold 10-20% of credits as a leakage and non-permanence ‘buffer pool’ – insurance – in case of fires, pests, or other potential factors that reduce net carbon storage. The revenue from the credits is shared equitably with project communities who decide how to spend it.

Reforestation & Afforestation

While we should prioritise conserving our existing trees, there are occasions when planting is a very appropriate course of action.

Reforestation is when trees are planted in an area from which they have recently been felled. It aims to restore forests to their previous state following degradation. Afforestation, on the other hand, refers to the planting of trees on land where none previously existed. It’s important not to be too literal here – don’t think never, think land which has not been recently deforested.

Unlike forest conservation, reforestation and afforestation both remove additional carbon from the atmosphere. As such, these projects generate removal credits and, if done well, can be extremely beneficial to local biodiversity.

Planting trees in urban environments can also be extremely positive. A recent study of 93 European cities found that raising tree cover by up to 30% (depending on existing levels), can reduce the average temperature by 0.4°C. This may sound minimal, but is enough to reduce heat-related deaths.

The big, blue problem

Spanning 72% of the earth’s surface, it is common knowledge that our oceans regulate the climate. Since 1850, the oceans and coastal ecosystems have absorbed a staggering 40% of anthropogenic emissions. Yet, as with forests, this ability to slow climate change is being undermined by human activity. Pollution, marine warming and overfishing all contribute to ocean and coastal degradation.

The brilliant, blue solutions

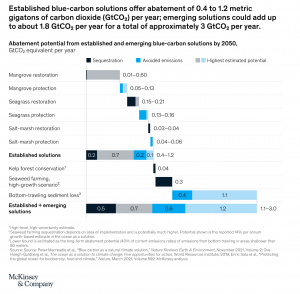

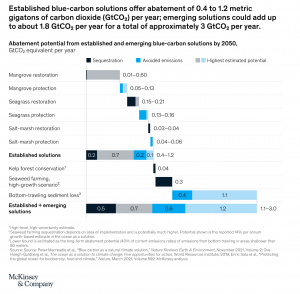

To fund the protection of these ecosystems, it is vital we invest in NbS generating blue carbon credits. Mangrove restoration projects – such as Delta Blue Carbon – are already sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, while seagrass has recently received attention for its enormous potential for capture. Indeed, McKinsey reports that even if we just used the currently established blue carbon solutions, they could remove between 0.4 and 1.2 metric gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere every year (see graph below).

(Source: McKinsey Blue Carbon report, 2022)

NBS ‘done right’

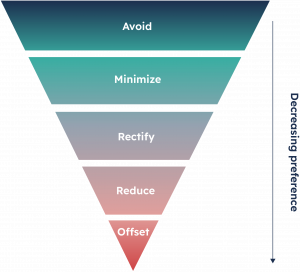

If implemented with integrity, NbS can help us to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, protect natural ecosystems and support the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. However, purchasing nature-based carbon credits is not a substitute for direct decarbonisation of the corporate value chain. Rather, investing in these solutions is a way for a company to faster meet, and eventually exceed, its emission reduction targets.

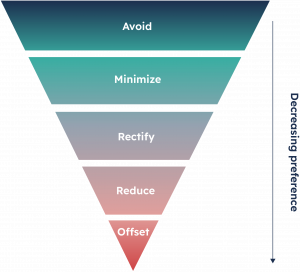

Indeed, prior to purchasing nature-based carbon credits, an organisation should already have set science-based climate targets and be implementing emission reduction in line with the mitigation hierarchy (see picture below). These principles are also outlined in the NCS for Corporates Guidance.

Now is a pivotal moment for NBS. Either we enter a negative feedback loop in which deforestation and ocean degradation become key drivers of climate change. Or, we engage in a positive cycle of capacity building and climate change mitigation. The second option is in reach – NBS are here now and readily available to scale – but urgently require funding. Buying carbon credits through the voluntary carbon market helps to channel this much-needed finance to high-quality NBS projects. Contact us to find out more about our portfolio of these high-impact, high-integrity climate mitigation solutions.